Click here for details

Currents

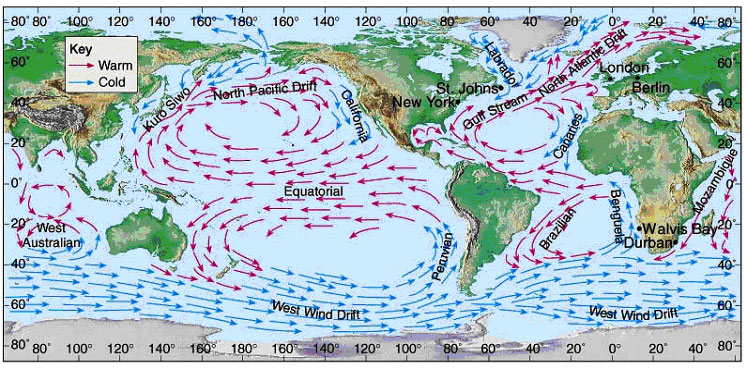

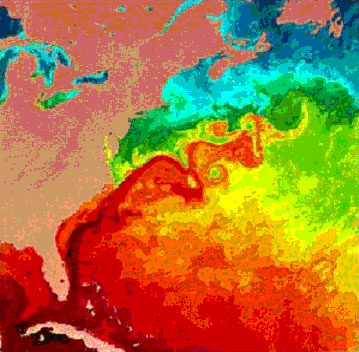

‘Current’ (or flow) plays a large, fundamental role in shaping the environment in which aquatic organisms live, feed and move. Surface currents are largely driven by winds and tides, while others deeper currents are driven by differences in densities and temperatures. Current is usually reported with a compass bearing in the direction the current is moving and a velocity (speed). This differs from the convention when describing wind direction, which describes the direction where wind is originating. Current velocities are measured in meters per second, which converts to 1.94 knots (nautical miles per hour). Globally, currents are responsible for redistributing heat (see below) from the equatorial to temperate and polar regions and have been used by mariners for centuries as ‘routes of opportunity’ for commerce, especially prior to the introduction of powered vessels.

Currents also help shape the particle size of bottom sediments with faster currents in general increasing the size of particles by carrying away the more easily resuspended, smaller particles. Currents deliver and remove nutrients and food to organisms fixed in place (e.g., barnacles, oysters), and are a direct physical force that organisms must face whether they are actively moving in the water column, subject to flows that they cannot swim against or fixed in place. Currents play a large role in determining the distribution of species (where on shoreline they can live), their morphological adaptations (feeding, attachment method), and behavior of most or all marine and estuarine organisms (e.g., Vogel 1994). Current directly and indirectly affects most aquatic organisms. The velocity of water affects sediment substrate (grain) size composition, as well as the delivery and removal of food, nutrients, and waste products.

For example, barnacles use a sieve-like structure, the cirral net to filter small particles from the surrounding fluid. When the water is still, the cirral net can be waved about to create the animal's own feeding current. However when sufficient water motion is present barnacles merely extend the cirral net into flow, allowing the ambient water motion to bring food to them. If waves or very rapid water flow (e.g., surf zone) barnacles keep their cirral net furled inside the shell, then extend the net during less stressful flows. For many small organisms living in a fluid is in many ways like living in a viscous semi-solid material producing significant drag (see work by Prof. M.A.R. Koehl, U.C. Berkley).

Body shapes and specialized structures offer clues to specific adaptations that allow organisms to cope with flows and currents. Attachment adaptations such as byssal threads, glues and other materials can serve to anchor invertebrates to the substrate. Body shapes that are dorso-ventrally flattened or streamlined in some other way allow organisms to minimize the force current exerts on them and maneuver with less energy expenditure. Mussels living on exposed, for example wave-swept shores have thicker byssal threads to better survive the impacts of constantly breaking waves.

The distributions of diatoms (microscopic plants), algae, and rooted macrophytes are influenced by current. Diatoms can be sorted into species by those that are adapted to slower versus faster moving water. Attached macroalgae appear to increase their abundance at sites with faster currents and hard substrates, while rooted macrophytes thrive in slower moving waters with finer (softer) sediments. The presence of rooted submerged aquatic vegetation (or SAV) baffles currents and slows down flow decreasing erosion and enhancing the settlement of fine, suspended particles. Diatom presence and associated morphology are strongly correlated with local current conditions, in part as a result of mixing and nutrient availability (e.g., Karp-Boss and Jumars, 1998).

Why measure current direction (heading) and speed?

Current measurements are important in the calculation of nutrient ‘loadings’ to a receiving water body. Current velocities are used to calculate fluxes. These are often used to calculate pollutant ‘loadings’ from a source water body to a receiving water body. RECON has a current meter off Fort Myers Beach (the receiving water body) which can be used to calculate pollutant loadings to the Gulf of Mexico when used in conjunction with a hydrologic model. The hydrologic model predicts current speeds and directions under a variety of wind and tidal conditions. In addition, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) operates and maintains two additional current meters in the tidal Caloosahatchee; one at Shell Point and another at Fort Myers. RECON stations were deliberately placed to take advantage of these existing devices to maximize the utility of the data streams for improved freshwater discharge management.

Karp-Boss, L. and P.A. Jumars, 1998. Motion of diatom chains in steady flow shear. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43:1767-1773.

Koehl, M.A.R., 1982. The interaction of moving water and sessile organisms. Scientific American 247: 124-132.

Koehl, M. A. R. (2007) Mini review: Hydrodynamics of larval settlement into fouling communities. Biofouling 23: 357-368.

Vogel, 1994. Life in moving fluids: the biology of flow. Princeton University Press. 368 pp.